by Alex Alford, USA deutsche Version

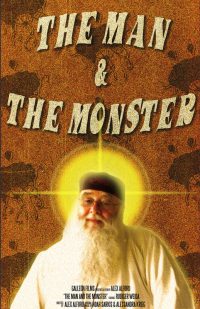

Film of 11min, German with English subtitles, at the end of the text.

It’s 9 o’clock on a cool, breezy October morning and I’m standing in the parking lot of a deserted train station two hours north of Berlin. I’ve come to the small town of Templin to visit Rüdiger Weida, or as he’s commonly known in Germany and on the internet, Bruder Spaghettus.

If you know Rüdiger, you know he’s in his 70’s and looks a lot like Santa Claus (except for his colorful collection of custom hats that his wife Connie makes for him). He’s got a strange job – he’s a disciple of Pastafarianism and founded Germany’s only physical church dedicated to worshiping the Flying Spaghetti Monster.

Those who practice Pastafarianism believe that the earth was created while the Flying Spaghetti Monster was on a drunken bender, and that’s why it’s so messed up. Instead of adhering to the Ten Commandments, you live by the eight „I’d Really Rather You Didn’ts“. And naturally, heaven contains stripper factories and a beer volcano. Pretty sweet, right?

Before this trip, I’d never been outside the USA, much less to a rural German town to meet with a man who spends his free time dressing like a pirate and singing parodies of traditional Christian hymns rewritten with more noodle-centric lyrics. But for my undergraduate film thesis, I had to make a foreign language documentary (never mind the fact that my German was non-existent at worst and miserable at best). However, I found myself captivated by Rudiger’s dedication to something that, to an outsider, seemed entirely crazy.

In the days leading up to my trip, I was nervous. My classmates teased me, joking that if I let the „pasta man“ take me out into the countryside, I might never return. As Rüdiger’s car pulled up to the station, I genuinely had no idea what to expect (having only previously communicated with him via email and one short phone call). But the first thing he did when he exited the car was greet me with a warm embrace. Upon learning that I had spent the night prior at a local hotel, he immediately said, „My friend! You should have called me! You could have stayed at my house.“ I knew then that I had made the right decision.

On the ride to his house, one thing was immediately clear: Rüdiger claimed his English was poor, but his English was light-years better than my German. So, we started talking. We discussed university, my time spent so far in Germany, and more. Upon arriving at his house – some ten minutes outside the city proper – he gave me the grand tour of his church. Church is a generous word, as it was a two-room building that used to house farm animals. It had no insulation and concrete floors. But then again, a church is what you make of it.

A large mural of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, which Rüdiger commissioned from a local artist, took up much of one wall. The altar was a rack for storing beer. Scattered throughout the space were all kinds of handcrafted ornaments from all over the world which spoke to the FSM in some way. In the other room, a table for meetings. Though the space was small and no-frills, it was immediately evident that a lot of care had gone into making the space feel like a holy one. One that, of course, had many cheeky nods to the satirical nature of Rüdiger’s work.

I had stumbled across an article about Rüdiger one day several months prior while researching potential subjects for my documentary. The story detailed the legal fight that had ensued after Rüdiger hung up signs detailing the ‘Noodle Mass’ schedule at the town’s main entrances. I thought the circumstances surrounding the town, the signs, the church, and the court hearing would make an excellent topic for a documentary. A plane, several trains, several emails, and a car ride later, here I was – and it was increasingly evident that what was the most interesting wasn’t the court case, but the man himself.

Over lunch – pasta made with mushrooms he picked from a nearby forest – Rüdiger spoke at length about the path that led him to the Flying Spaghetti Monster. His love for satire started as a university student growing up in post-WWII East Germany. Speaking out against the government politically was frowned upon, so Rüdiger and his friends turned to satire as an outlet for their criticisms. They wrote poems and read them at local carnivals. They even took more extreme measures – in an effort to protest mandatory military classes for students, Rüdiger and several classmates hung signs across campus in the dead of night, proclaiming, “Get the military out of our schools!” Rüdiger told no one, except for one of his closest friends. Unfortunately, this friend happened to be a political informant for the Stasi, the military police.

Rüdiger and his friends were surveilled by the government: their whereabouts were tracked, their photos secretly taken, and their apartments bugged. Rüdiger’s secret government profile eventually amassed over 800 pages. He decided to leave the town.

Now, decades later, Germany has reunified and Rüdiger has found a new institution to target: the church.

I was fascinated by Rüdiger’s story and the way his past informed his present. As I suspected, there was much more to the “noodle man” than had previously met the eye. For the rest of our time together that day, I did very little filming. Mostly, we talked – about life, the church, and of course, pasta. It wasn’t until a month later that I would return to shoot the actual documentary.

That next month, I spent four days with Rüdiger. I interviewed him extensively, but also got to know his daily life. He’s retired, and spends much of his day tending to his garden. He cooks, and is also an avid photographer. We went through his Stasi file. Although I asked the questions in English, Rüdiger would respond in German to best articulate his answers. This meant that I had no idea what I was capturing until I met with a translator the next week. To compensate for this, I had to ask him a lot of questions, and I’m thankful that he put up with my constant questioning for so long.

In the end, this long and strange road led to a film that we are quite proud of. It is a portrait of a man that, up until now, wasn’t seen in the news. Sure, Rüdiger’s antics with the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster may seem strange at first, but it’s quite different when given context. As a youth in East Germany, Rüdiger often criticized but was unable to offer a solution. But now, in retirement, he has found a way to not only criticize, but also create a community. To be Pastafarian surely means to criticize organized religion; but it also means to find joy in life. It means to come together. To enjoy our time on this earth with good friends, good beer and, of course, lots and lots of pasta. The world is full of people with interesting stories to tell. All we have to do is be open to listening to them.

So hat Bobby Henderson ein Feedback, wie in Germany seine Idee multipliziert und immer weiter ausgebaut wird.

Zur Feier, dass der Film wirklich zustande kam, öffnete ich sofort eine Büchse Fleischklößchen. Blöderweise mit Reis, wie ich zu spät feststellte. Zum Glück ist das Spaghettimonster tolerant und übersieht diesen Lapsus..

Bierelujah!

Lasst uns, unseren Krug erheben, auf den „pasta man“ aka Bruder Spaghettus.

#Legende

RAmen!